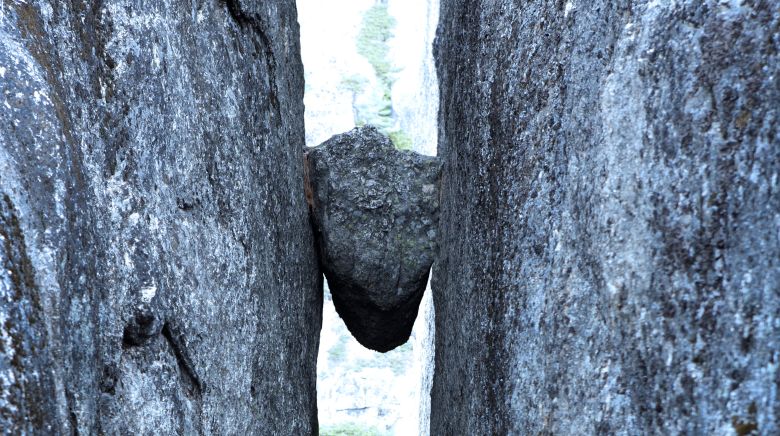

Between a rock and a hard place

15 December 2022 | news

By Chris Whelan

Chief Executive

Universities New Zealand – Te Pōkai Tara

The annual reports of all universities showed a surplus last year. Yet all are also saying they can’t lift salaries for their staff in line with inflation.

So what’s going on?

The Tertiary Education Commission (TEC) requires all publicly funded tertiary education providers to generate small annual surpluses as one of a number of metrics that indicate effective financial management. Typically, a 3% surplus (calculated as net surplus divided into gross income) is the figure most often suggested as the target.

Why 3%? And what happens to the 3%?

The answer to both questions is the same. 3% is about the average amount costs rise in a normal year for education providers. This year’s surplus is used to pay for next year’s cost increases – rising salaries, building costs, etc. The surplus must ultimately fund all operational and capital expenditure.

Of course, this isn’t a normal year and costs are rising far more than 3% at present.

In broad terms, university finances are heavily influenced by the following factors. Note that these are averages across all eight universities and numbers vary between universities.

- 58% of all university revenue comes from students. A fifth of that is from international students and four-fifths are from domestic students.

- 28% of university revenue comes from research. Four-fifths of that are through research contracts that mostly pay on completion of milestones or contracted deliverables. If the research projects run late, payments are slowed down. The salaries and wages earned by research staff continue to be paid, however.

- 57% of university expenditure is associated with personnel – salaries, ACC levies, superannuation contributions, etc.

Most importantly, however, 77% of all university income is controlled by the Government. This includes 90% of all research funding, and domestic student fees and other tuition subsidies, where the Government decides how much they increase annually.

The financial position of each university varies markedly, but all are seeing:

- Government has limited fee and tuition subsidy increases to 2.75% – less than half inflation.

- Flat domestic student numbers.

- Strong pressures to increase salaries to help staff deal with cost-of-living pressures caused by high inflation and high interest rates.

- International student numbers well down. And, even if first-year numbers rebound quickly back to pre-Covid levels, universities are still missing second-, third- and fourth-year international students.

- Research projects have been stretched out over longer time periods thanks to closedowns and other Covid-related disruptions. Income has been delayed but universities have had to keep paying researcher salaries.

- The costs of maintaining and where necessary building new infrastructure rising much faster than inflation.

Universities are all taking decisions necessary to successfully get through the next three to four years – a period when costs are expected to keep rising rapidly and there are few realistic options for increasing income to compensate.

Image: iStock